School Watch: Geartrain Boring

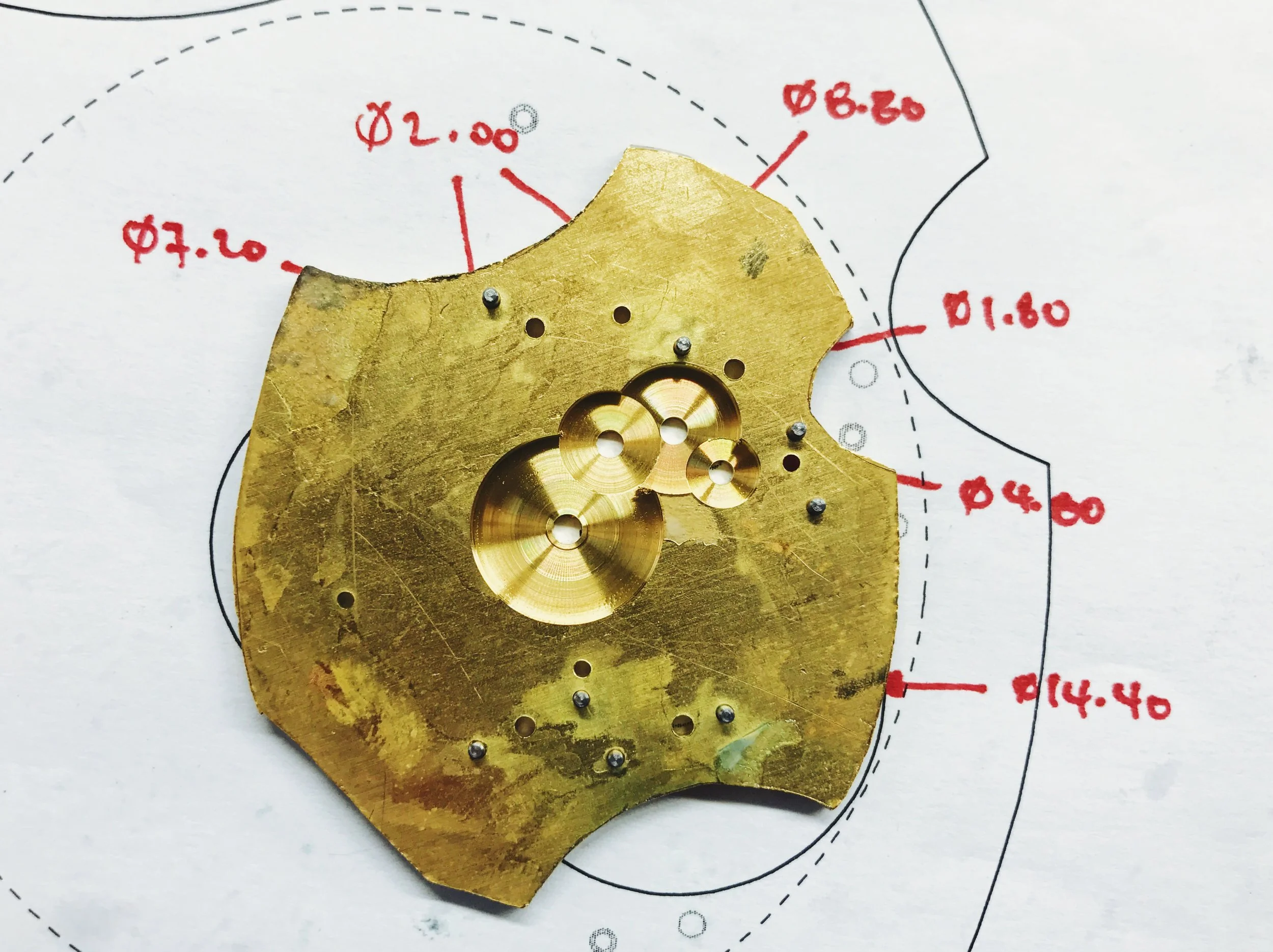

We're already working on the heart of the school watch project: cutting the recesses for the geartrain and jewels.

If these watches were serially produced, these recesses would be formed through milling. Since milling isn't a part of our curriculum, we'll be using the faceplate to bore the recesses open on our lathes.

The first step to cutting a recess is to mount the mainplate on our "bridge" via the steady pins and center the target jewel using the faceplate and your choice of centering device. Then the mainplate comes off and it's time to start machining.

It's possible to bore into a flat surface, but it's time consuming and hard on your cutter. Instead, we'll drill a pilot hole and use that as the backbone of the boring operation.

Like any drilling at the lathe, start by using the graver to prick punch a dimple into the workpiece for the drill bit to follow.

It's a little disconcerting to prick punch such an irregularly-shaped object (usually the dimple goes right in the middle of a circular workpiece), but it's the only way to guarantee centricity.

The target diameter for this hole will eventually be 1.90 mm—the jewel is 2.00 mm wide, and will be brought to size with a watchmaking reamer. I drilled at 1.60 mm to give myself enough room to feed the cutter into the workpiece, while still leaving enough uncut material to get fully centered and circular through boring.

Boring operations like this are easiest to do with a double-sided cutter. The jewel recesses require a very small cutter (0.70 mm), but the geartrain recesses are big enough that I can get away with a cutter of about 2.00 mm or so. It's significantly stiffer and easier to use. With both tips ground onto the same edge of the cutter, you can set your cutter height and flip it around without having to recheck, something that would be impossible with boring like this.

Once the geartrain recess is cut to size, I can just flip the cutter around and use the thinner tip to bore out the jewel recess. 0.30 mm isn't much to cut, so it doesn't take long at all. Drilling any more undersized would increase the machining time, though it would minimize the potential for error. It's a trade-off.

With the proper cutter shape and position, this flat brass stock gives off a nice rainbow effect when the surface finish is applied carefully and correctly.

Chamfering the recesses can be done by hand later or with the cross slide now. These aren't visible surfaces, so the finish isn't as important, but I like the look of properly machined bevels (though a hand tool is required to remove the tiny carryover burrs you can see on some edges between recesses). While we'd usually use the graver to cut bevels at the lathe, it is impossible to do it properly with a workpiece like this—the gaps between intersecting recesses would cause the tool to jump and make a huge mess. It's the cross slide or nothing, here.

Just the balance wheel recess to go, and then it'll be time to cut out the bridges!

Watchmaking student at the Lititz Watch Technicum, formerly a radio and TV newswriter in Chicago.