Vintage Oddity: "Resevoil"

Here's a whimsical piece of horological history: a remnant of the "fake jewel" era of mechanical watch marketing.

Jewels are used as low-friction bearings in watches, and fully-jeweled (or mostly-jeweled) watches are the standards in precision timekeeping. A fully-jeweled hand-wound watch will have 17 jewels, including 5 on the balance, 4 on the pallet (2 stones and 2 pivots), and 2 each on the escape, 4th, 3rd and center wheels. 15 jewel watches, which use bushings on the center wheel, can also keep just as good of time, since the center wheel is a high-torque component, and isn't as susceptible to frictional losses.

As a marketing ploy, watch companies would sometimes artificially inflate the jewel count of their movements by putting nonfunctional jewels into nonbearing areas. This Resevoil, which I found in a box of scrap movements in a classroom closet, is one of those tricksters. I noticed it immediately, thanks to the prominent cap jewels over the geartrain and the effusive engraving that goes with them.

1957 advertisement, via eBay

The Resevoil system was marketed as an addition that gives the "service and greater accuracy of a 21 or 25-jewel watch" by adding additional "oil reserve" jewels. The ad copy is light on details when it comes to exactly how the system works, which is probably for the best.

Capped geartrain pivots have significantly lower friction if properly implemented, but these are suspicious. The first hint that something is amiss is the lack of cap retaining springs, meaning that all four caps would have to be installed simultaneously with the bridge. The second clue is that the caps are eerily blank, and seem to hover above nothing.

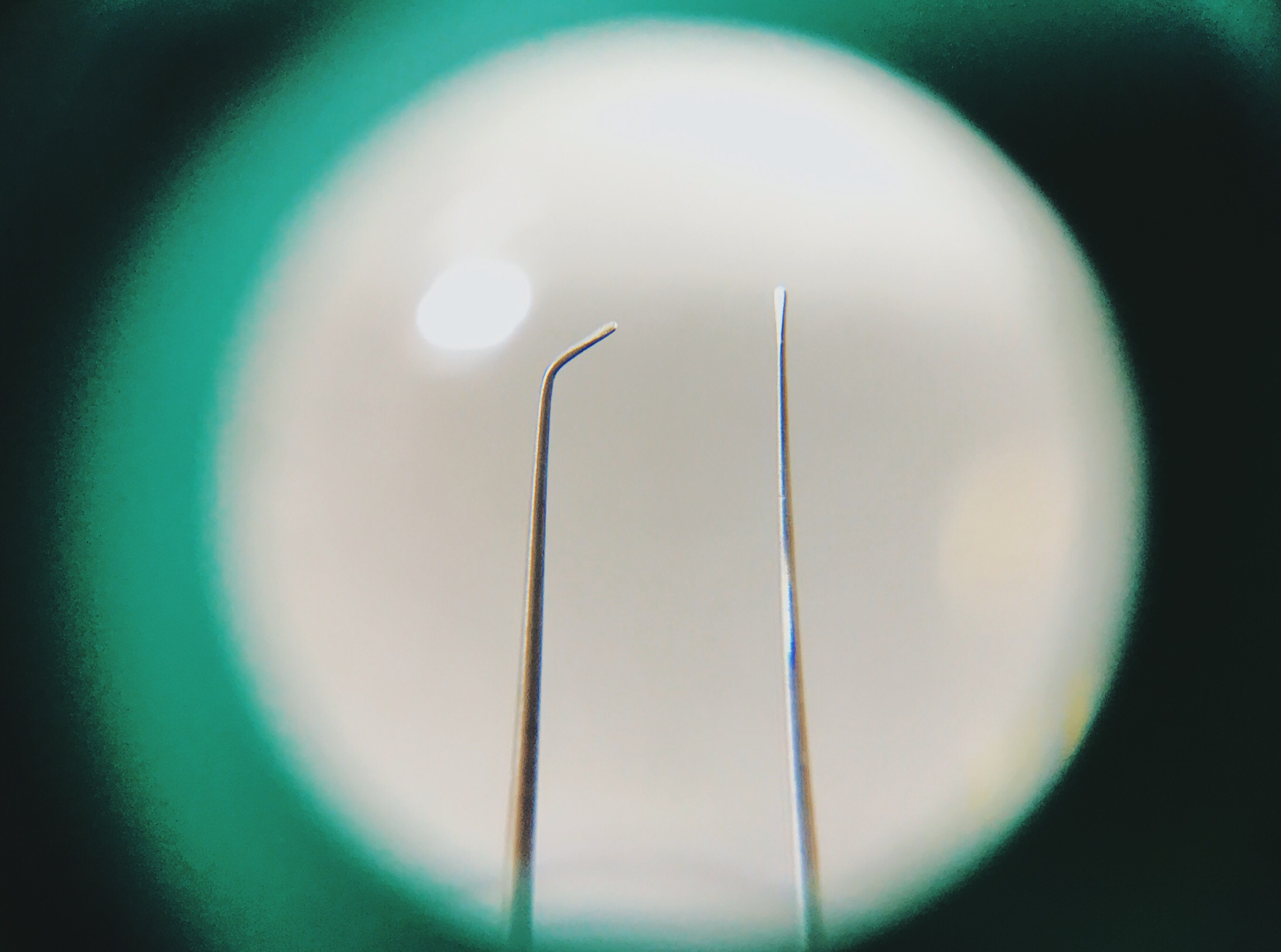

Real cap jewels serve as the pivot's axial bearing surface, and the pivot is visible beneath them (as seen here, ironically on the other side of the movement).

The plate starts to slip immediately upon loosening the screws, and it comes completely off to expose the real train bridge beneath... Complete with a different company's engraving!

Upon inspection, the caps reveal themselves to be purely decorative. The jewels are recessed at seemingly random depths into the plate, and are surrounded by horrible burrs. Even if the geartrain pivots could possibly reach to the recessed cap surfaces, the oil would never stay put.

Besides, the pivots don't even come close to clearing the top of the oilsinks. Their axial bearing surfaces are the shoulders of the wheel arbor, just like any normal geartrain pivot—or the 17-jewel Hilton that the fake caps sit upon.

Little information is available about Hilton, but a comment on Watchuseek's forum suggests that they eventually got into hot water for this fake jewel business:

Hilton was a company based in New York City. Hilton distributed watches usually made with 17 jewel Swiss movements and cases from a variety of sources including Hong Kong. It was a marketing company rather than a manufacturer. Hilton got in trouble with the FTC in the early 60s over misleading pricing and claims for their watches -JimH, Feb. 25, 2009

What does this mean for the watch? Nothing. While it might have been an eyebrow-raising choice 60 years ago, nowadays it simply makes the movement a charming oddity. The base movement appears to good quality and Swiss made, which should work well for an older timepiece. As for this one specifically, it's back to the closet until it's needed for parts!

Watchmaking student at the Lititz Watch Technicum, formerly a radio and TV newswriter in Chicago.