Micromechanics: Precision Abrasives

The lathe is precise to hundredths of a millimeter, but for steel friction fits, where thousandths of a millimeter can make or break a project, we need even greater precision.

The solution is, perhaps strangely, sandpaper. To be precise, it's lapping film, but the principle is the same. It's a paper/film coated with tiny abrasive particles which we use by hand to precisely remove minute amounts of material from a workpiece.

Our lapping film comes in a variety of grits, measured in microns, or μm. One micron is equal to one thousandth of a millimeter. For reference, a human hair is roughly 10-50 μm wide, and our lapping film comes in grits as fine as just 3 μm.

A 6 μm carbon filament resting against a 50 μm human hair (Wikipedia).

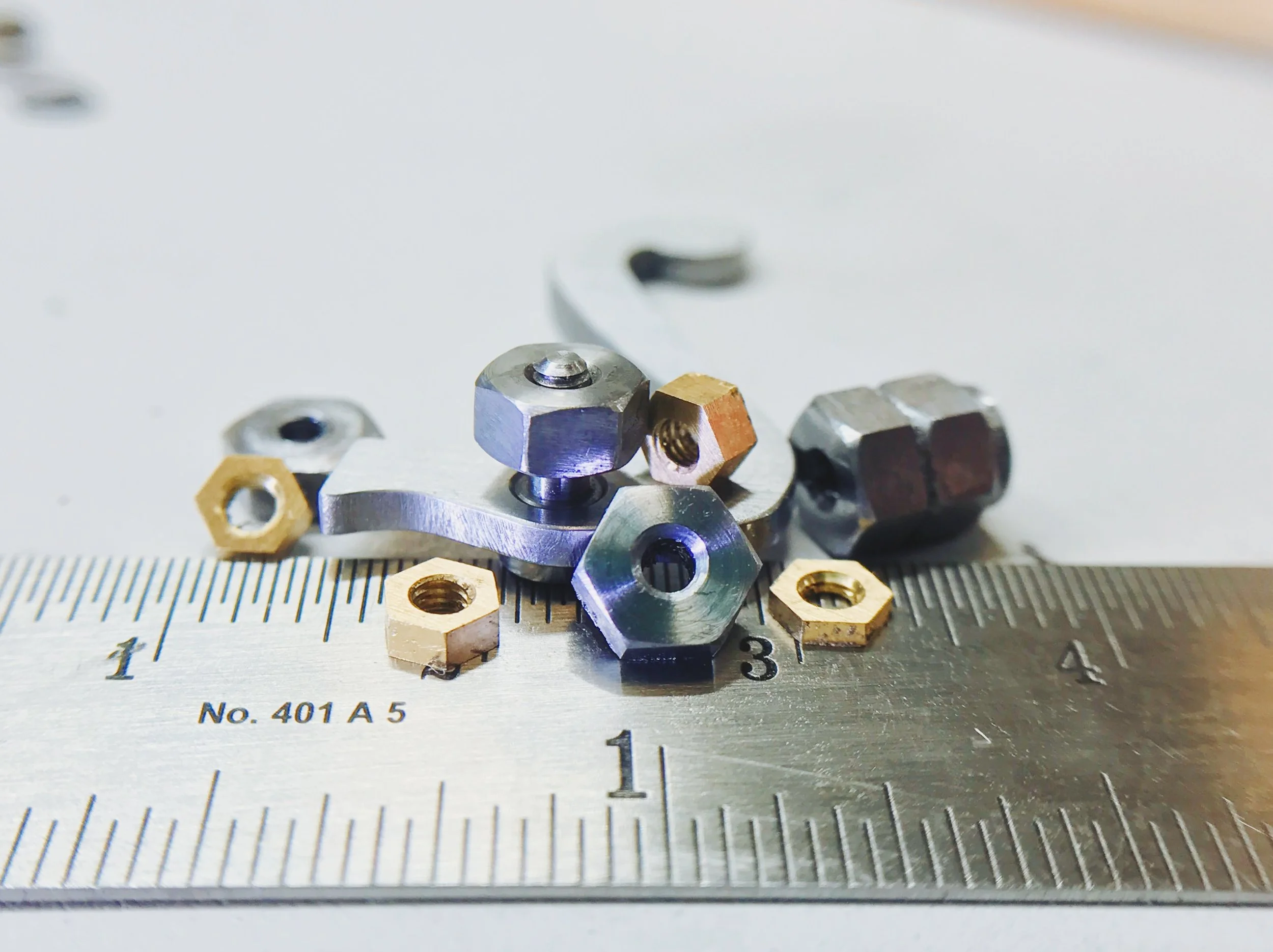

For the clock project, we need to repivot the week wheel, since our clock plates are a different distance apart than the original design. This means we have to cut out the original pivot and create a hardened and tempered steel pivot to replace it.

With our micrometer, we're able to measure to about the nearest 2.5 μm, so that's the maximum precision we're going to be able to achieve. 5 μm in either direction will cause the pivot to fall out (too loose) or it won't go into the wheel in the first place (too tight). There's absolutely zero tolerance.

To achieve this perfect fit, we machine the pivot to about 0.01 mm above our target and use the lapping film to reduce it to the proper diameter. Since this is heat-treated, the abrasives also remove the visual effects of the heat treatment process.

You can see the "bluing" and scale (carbon deposits) from the heat treatment process on the outside of the repivot piece in the header image. That will also be ground down with the lapping film to create a seamless finish.

Lapping must be done with great care. The film is mounted on a brass carrier, which we must file perfectly flat and square, and is held against the workpiece while it's mounted in the lathe. It's delicate work—going under dimension means we'll have to remake the entire piece—but done properly, it enables us to achieve incredible precision, all by hand.

Watchmaking student at the Lititz Watch Technicum, formerly a radio and TV newswriter in Chicago.