Micromechanics: Brass

Almost all of our micromechanics work will involve metal, and with rare exceptions, that means brass and steel. We begin with brass.

Brass is the backbone of watchmaking—and indeed, most watches! The bridges and plates that form a given movement are (with rare and expensive exception) made of plated brass, and many of the gears (wheels, in watchmaking) are made of brass as well.

Brass has many desirable qualities which make it common in watchmaking, but there's one that stands out for a beginner: It's soft. We tend to think of metals as hard, but hardness is a spectrum, and brass is on the soft side, making it easy to machine and file. Cutting tools last longer and cut faster when working on brass, and for a novice, it's much more forgiving.

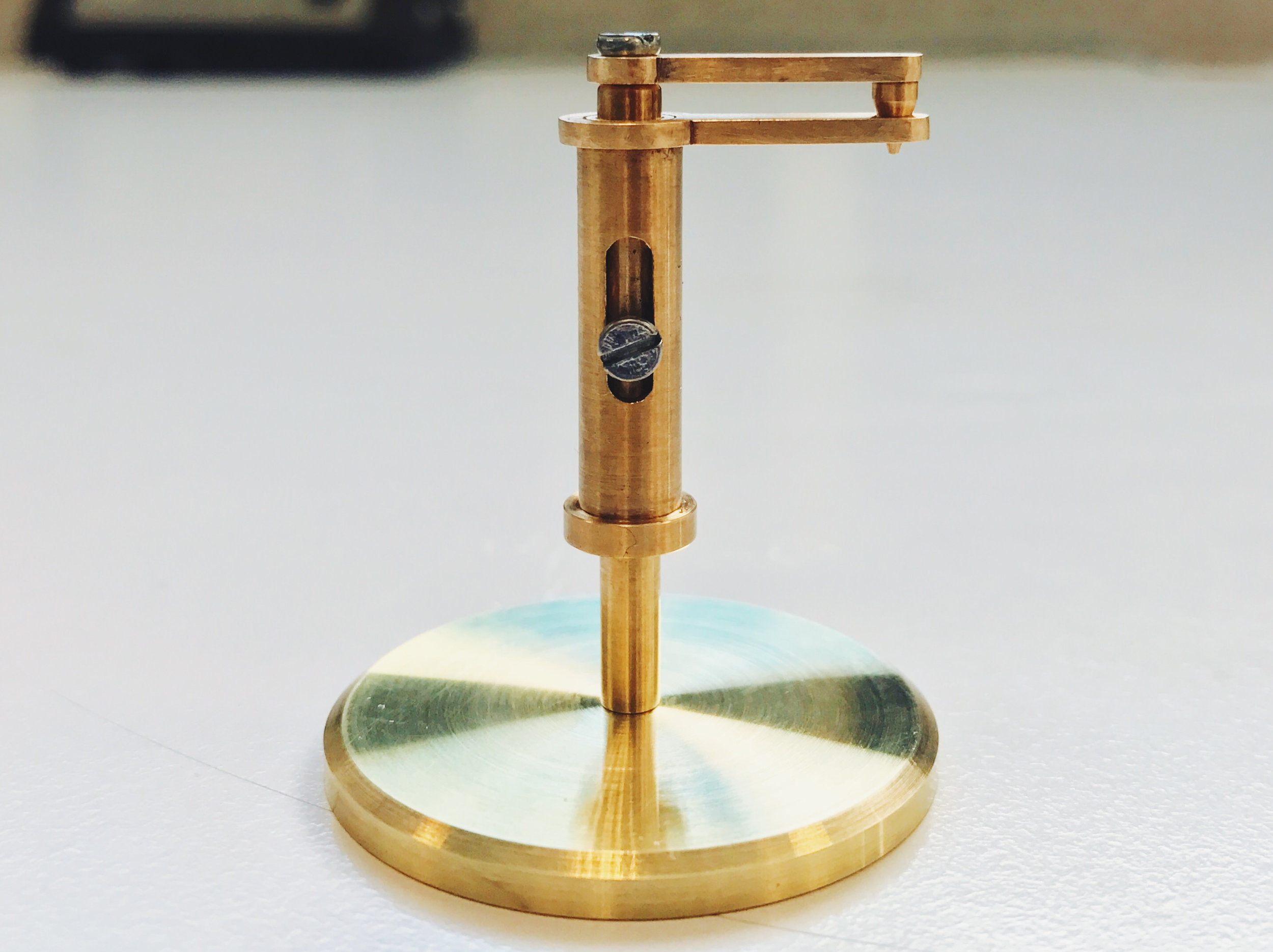

This first piece is a simple square, cut and filed to within 0.1 or 0.05 mm of their specified dimensions. The center has a threaded hole, which will be used to support the functional half of this tool later on.

There's a lot going on with such an apparently simple piece. First, it must be cut and filed to dimension. Then it must be precisely drilled, tapped and chamfered. Finally, it must be finished and beveled (if you look closely, you'll see a raw file mark on the left bevel—points off!). Just this tiny 30 mm square took a full eight hour school day to complete.

Watchmaking student at the Lititz Watch Technicum, formerly a radio and TV newswriter in Chicago.