Burnishing

Vintage watches almost always have worn and damaged parts. It's a simple fact of life and tribology, and cannot be avoided (unless a watch is kept in a safe for its whole life). Worn parts must be either replaced or repaired, and sometimes spare parts simply aren't available.

Burnishing is a delicate and complicated but extremely effective way to repair damaged pivots. As pivots wear, troughs and mounds appear on the metal surface—burnishing pushes the high points into the low spots, simultaneously smoothing and work-hardening the surface.

The traditional tool to burnish pivots is the jacot tool, a kind of miniature hand-powered lathe. The tool has a driving end, powered by a bow, and a bed end.

The bed is graduated by pivot diameter. Smaller pivots are graduated by half millimeter, and larger pivots can be graduated by two millimeters or more. The smaller the pivot, the greater the precision required. A bed marked 14 will be 0.14 mm deep precisely. Burnishing will end as soon as the pivot hits 0.14 mm. This poses a challenge to the watchmaker: a smaller diameter bed will allow quicker burnishing, at the expense of fewer safeguards against removing excessive material.

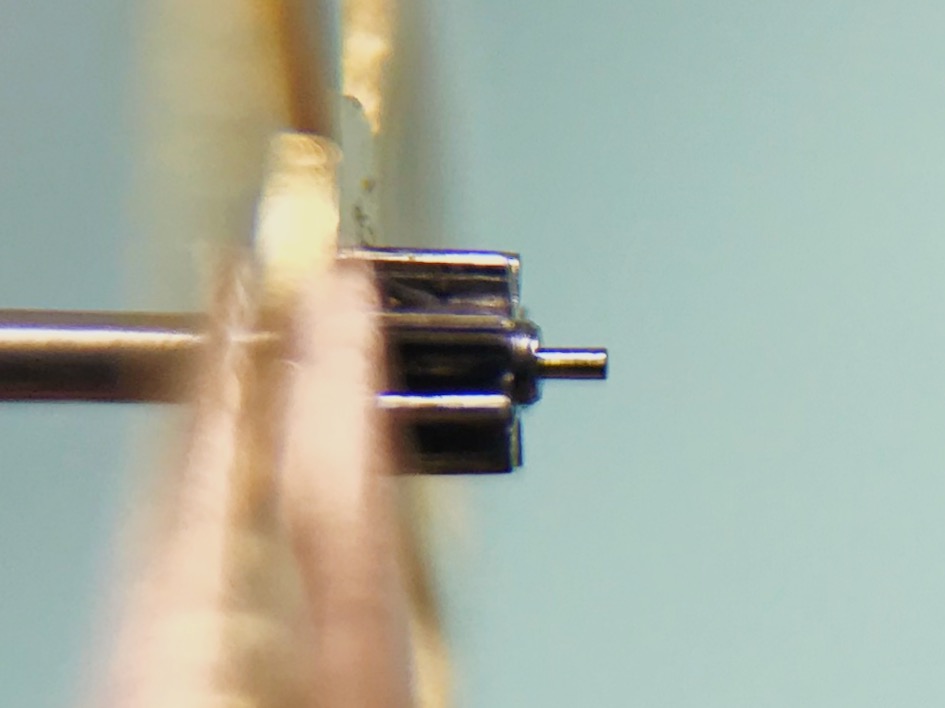

This pivot measures 0.135 mm, so a 13 bed will be a safe and conservative choice.

Wheels mount in a female center on the driving side, and into the bed on the other side. The driving center will ideally bear on the arbor for optimal strength, but this tool's selection requires the center to ride on the pivot. That's ok, but it will require greater care while burnishing to keep things from bending.

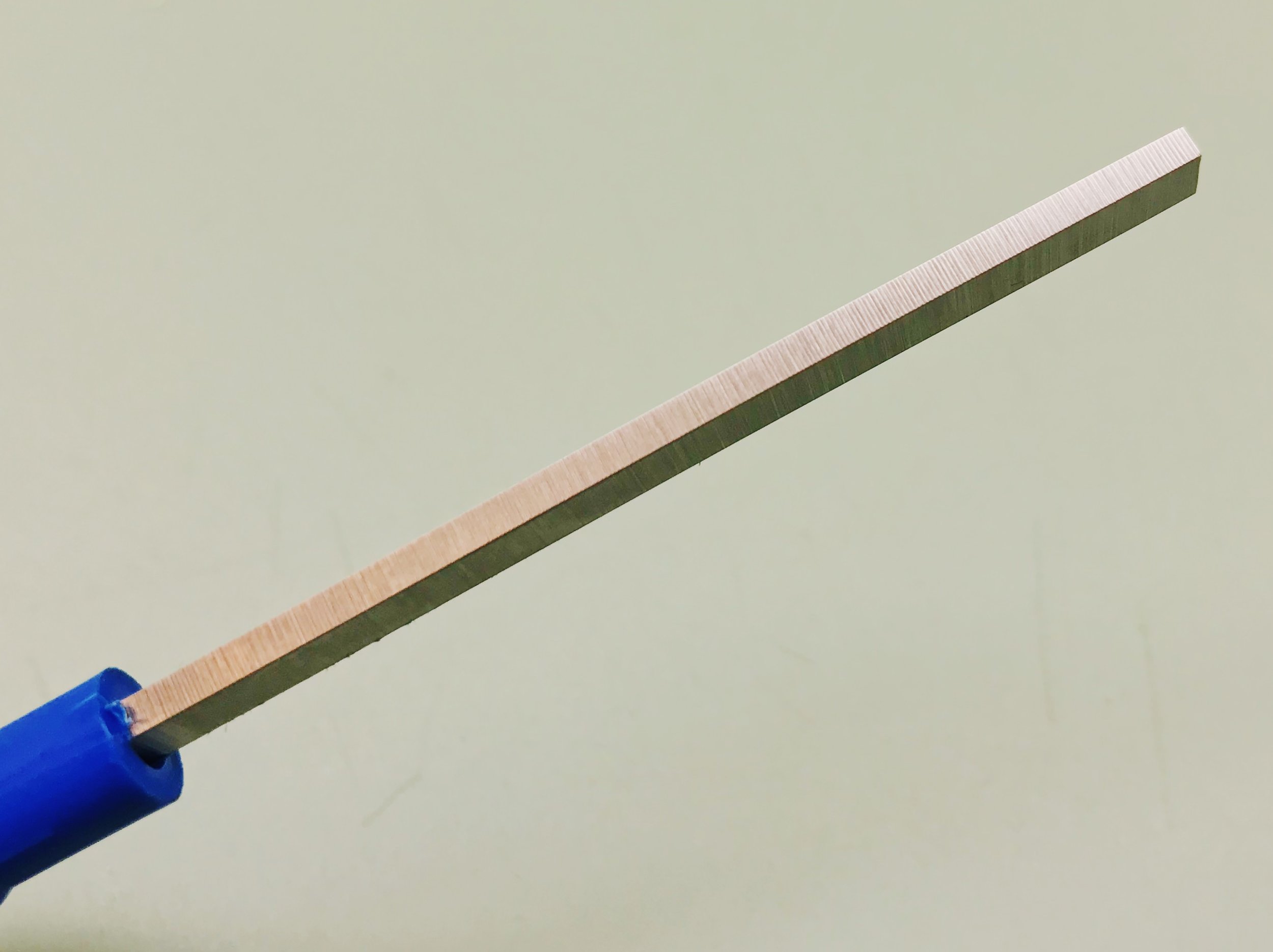

The burnisher itself is a simple thing. The shank is a precisely-ground bar of hardened and tempered steel, which has a fine perpendicular grain.

It's mostly trapezoidal, with a curved edge on one side for conical pivots (like on balance wheels). We'll come back to those in a later post.

I'm overhauling a Universal Geneve Polerouter, which has a calibre 69 microrotor movement. It's an awesome watch, and I'm lucky to have a collector trust me enough to work on it. The watch came to me in need of a service, and had some pivots in need of repair.

The great and third wheels were the most worn, and the third wheel most of all. The pivot is badly scored near the shoulder, and is noticeably narrower (at high magnification) than the rest of it.

Burnishing is an extremely simple process, yet difficult to master. The jacot tool doesn't clamp anything, so the wheel is constantly floating loose between the center and the bed. The burnisher is the only thing keeping things where they should be.

To work properly, the burnisher must be run back and forth, perfectly perpendicular to the bed, while the bow drives the wheel back and forth in opposition. The burnisher must be held perfectly square the the shoulder as well, or else it will grind in a taper.

Burnishing is a very slow process, but it does remove material. Real-life repairs always require a balance between perfection and reality. If scoring is completely removed, it might remove so much material that the pivot begins to have too much sideshake. Instead, some surface finish might sometimes be sacrificed in favor of pivot diameter.

This pivot was burnished until the voids were filled and the shape of the pivot was repaired, but not until it was completely perfectly polished. That's ok. The watch was running decently before the repair, and it will do even better now! I'll be posting more about the Polerouter's repair soon.

Watchmaking student at the Lititz Watch Technicum, formerly a radio and TV newswriter in Chicago.